ACADEMY HISTORY

early academy history

Late in the 19th century, the Edmunds-Tucker Act prevented Mormons from holding public office, including that of teaching in public schools. Mormons were concerned about the anti-Mormon philosophies their children were receiving in state-run schools, so they began an intensive effort to build their own educational facilities from Canada to the Mexican colonies.

Over 30 academies were built for this purpose, including the Brigham Young Academy in Provo (which was recently restored into a magnificent public library for the community) and the Oneida Stake Academy in Preston, Idaho. The Oneida Stake Academy is one of the oldest, having been organized in 1888 in Franklin. It was held in a room above a store there for 3 years.

In 1890 Solomon H. Hale was called by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints to be the superintendent over the construction of a new, rock building five miles north of Franklin, in Preston, for the academy. A year later, classes were held in its just-completed basement. The building was finished in 1895, dedicated by Moses Thatcher on July 28, 1895.

Hale was an ecclesiastical leader in the Oneida Stake presidency. He was the first counselor to George C. Parkinson. Mathias F. Cowley was the second counselor. His assignment included raising funds locally and, in the case of subscriptions obtained in the form of livestock and produce, convert them into building materials and labor. Hale not only supervised this project until its completion five years later, but served as a member of the board of education of the institution for 15 years afterward. His children attended the school. At the time he was called to be the superintendent of the project, he and his family lived in Gentile Valley where he ran cattle and horses on his ranch. Due to his involvement with the academy he soon decided to move his family to Preston. He built and sold three homes in the city of Preston and ran a ranch with his son three miles south of Preston.

John Nuffer was the head stonemason. He and his young wife, Louisa Zollinger, were living in Glendale (about five miles from Preston) amongst other members of Nuffer’s family who homesteaded there. The calling required his full attention, so the young family moved to Preston as the Hale family did.

Although the plans for the academy came from church officials in Salt Lake City, Nuffer, who apprenticed in the city of Stuttgart, Germany, “modified the design considerably, accounting for its beautiful Gothic appearance,” stated one of his sons, Myron, in a letter to Newell Hart and reprinted in the Cache Valley News published by Hart between 1969 and 1982.

The stone from the building came from Nuffer’s brother, Fred. He ran a quarry on his property 10 miles up Cub River Canyon from Franklin (six miles from Preston) on Sheep Creek. Stone from the quarry was used “on the better buildings going up throughout the neighboring towns,” including Logan, where it was used to build the college and sections of the Logan Temple. “The contract to build the academy called for 2000 cubic feet at 25 cents per foot. The stone was used for corners, sills and water table. “All work was done by hand. … We used 12-foot churn drills and blasted large blocks loose from the main ledge. We had to be careful how much powder we used so as not to shatter or cause seams in the stone. “We usually had to put a second charge in the opening made by the first charge to dislodge the block from the man ledge. The block so dislodged was from six to seven feet thick and about 20 feet long. From then on all tools used were hammers, axes, wedges and squares. “Grooves were cut with axes where ever we desired to split the block, then wedges were set in the grooves about 10 inches apart and driven in with hammers. Then we dressed them down to the right measurement, allowing one half inch for the stone cutters to take out all the tool marks we made.” (Statements of Fred Nuffer published in Cache Valley News #45, 1972.)

Nuffer and Joseph S. Geddes built many buildings in Franklin County. They built several residences, the Weston Tabernacle, the Preston First Ward chapel and several school houses. He was the architect for most of the older business blocks in Preston, the Opera House, the Idaho State Bank Building and the Oneida Stake Science Building (later known as the ag/art building at Preston High School.) Except for the Weston Tabernacle, all the public buildings are now gone.

Former student, Scott Nelson, who graduated in the 20s, wrote the following to Newell Hart: “My father, while a student at Brigham Young Academy, was called into Dr. Karl G. Maeser’s office and told that he had been nominated to open a new academy in Southern Idaho. But he had “a choice of accepting or continuing his studies at BYA.” Next day Father reported his decision: He’d rather not go. But Prof. Maeser shook his head and said it was too late. The Lord, through his Servant here on Earth, had decided that Bro. Nelson was just the man of the Preston Assignment.

“Having thus “volunteered” Father and his wife, Almeda, with year-old-daughter, Mae, headed north … “We arrived,” Father recorded, “in what the conductor announced was Preston, but there was no depot in sight as our trunk was tossed into a barrow pit beside the track. “Father and young Meda, my mother, was the entire faculty. Nobody raised the question of teacher’s pay, and the new teachers probably had to depend on money volunteered for tuition. Father was not specific about the salary paid, but it couldn’t have been over $50 a month, if that. All church property had been confiscated by the Government and no appropriations were possible from that source. [Edmunds Tucker Act] Students paid “tuition” they felt they could afford, and nobody was denied admission for lack of money. (Many failed to pay a cent for their entire stay at the academy, although several of these students went on to acquire doctorates, Father implied). Townspeople brought wood for the stoves, and on a specified day the boys chopped the wood and the girls set up food for the workers.

“All social functions were school-supervised and “were of such a high order people deemed it an honor to be invited.” “…Students came from Pocatello, Gentile Valley, and all settlements south to the Utah Line. Father described his students as roughhewn diamonds from cattle ranches and farms who were transformed form shy and awkward youths into cultured students. “Most of the charter members came back for the second and third years and from this group emerged bishops, counselors, mayors, county and stake leaders…” “The basement of the new school was sufficiently ready to house the school in 1891-92, and the upper building was finished by 1895. Other teachers were added, but Father ruefully observed, “ I taught in this school for several years with scarcely any pay.”

Academy History Since 1922

When the Edmunds-Tucker Act was repealed in 1922, the Oneida Stake Academy reverted to state ownership and became Preston High School. As the school district’s need to grow advanced, additional buildings were constructed, until Preston’s present high school was built in the 40s. When the present high school was built, it was located approximately 15 feet in front of the Oneida Stake Academy’s front door. It was so close, the academy’s staircase had to be remodeled. The academy became an auxiliary building to the high school.

Classes were taught in the academy, but the building began falling into disrepair in the 60s and 70s. In the 80s, under the direction and vision of valley historian, Newell Hart, efforts to restore the building succeeded in making it available not only to the school, but the public as well. The arts had a magnificent home in the Oneida Stake Academy. Concerts, art shows, wedding receptions, etc., were held there. Under the direction of Donna Shipley, a community art club was formed that met there. Basement rooms of the Oneida Stake Academy were used as a weight room for the high school until the late 90s.

At that time, the academy was more or less condemned and the school district began looking at the space it occupied as prime real estate for a desperately needed new cafeteria and library for the high school. The school board finally put a deadline of March 2003 on any efforts to save the academy from the wrecking ball.

Joseph Linton, a local architect, had rounded up enough grant monies to pay for a feasibility study that confirmed the academy was structurally sound enough to save, so a hunt began to find a mover not only capable, but interested in taking on the project. Dennis Lindsay, second generation owner of Lindsay Moving & Rigging, Inc., in Washington, was one of the movers that inspected the site and entered a bid for the job. Then the fund-raising began.

A loosely knit group of Preston residents, with the help of the Mormon Historic Sites Foundation (whose president, Kim Wilson, attended classes in the academy), began in the summer of 2002 to search for over $1 million to cover the bids to move the building. About $200,000 had been identified for the project, but the March 2003 deadline came and went, and the group had little more than the $200,000.

As the school district began making plans to demolish the building, the trustees allowed the group to continue to try to raise the money to move the building. That’s when the miracles began happening. First, Larry Miller, of the Utah Jazz, pledged $250,000 to the project. That was followed by two $100,000 pledges, another $250,000 pledge and $100,000 in individual pledges from local people. Work on the actual move began in August of 2003. The building was moved in December of 2003, and is now under restoration efforts.

To Mormon pioneers, education was a priority. Many of the institutions they started continue to educate students today. Some of the leaders the Oneida Stake Academy produced were two presidents of the church: Ezra Taft Benson and Harold B. Lee, a United States Secretary of Agriculture: Ezra Taft Benson and a Hall of Fame FBI agent: Samuel Cowley. Utah State University president E. G. Petersen and former Ricks College (now known as BYU-Idaho) president Joe H. Christensen gained their educational background within the walls of the Oneida Stake Academy as well.

Notable Attendees

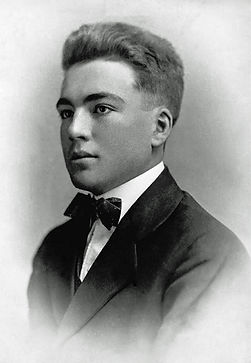

Harold B. Lee and Ezra Taft Benson were classmates at the Oneida Stake Academy in the late 1910’s. Both became President of the LDS Church. Other notable attendees were Joe J. Christensen, Richard Edgley, Spencer Condie, E. G. Peterson (President of USU), Samuel Cowley, and many other persons of achievement in the world.

glow.png)